Why the California "Builder's Remedy" Means What It Says

/We’re a week closer to the housequake. This week: why we work with untested law, a plain reading of the builder’s remedy, and a special invitation.

“No One … Underst[ands] the Full Scope” of Housing Reform

Over the weekend, Ezra Klein wrote in depth about Los Angeles’s failure (so far) to build “affordable” housing at less than $600,000 per unit. It’s a great article. In 2016, Los Angeles voters approved $1.2 billion to construct 10,000 new homes. Six years later, just a third of those homes have been built, at a cost north of $2 billion (the city doesn’t fund all of it), and the slow progress is being debated in the Los Angeles mayor’s race. Klein’s article raises excellent questions about why affordable housing is so hard.

The most important part of the affordable-housing equation is time. No one can build a home overnight. Even if there were infinite land and no laws to delay housing production, it would still take time to line up the people and materials builders need to make a new home. Then, if there’s no supply crunch, homes become cheaper with age, as mortgages get paid off and original owners vacate for newer buildings. Jane Jacobs wrote a chapter on this phenomenon in her magnum opus The Death and Life of Great American Cities (see ch. 10). And that’s to say nothing of the fitful way funds are Frankensteined together, which Klein covers in his article.

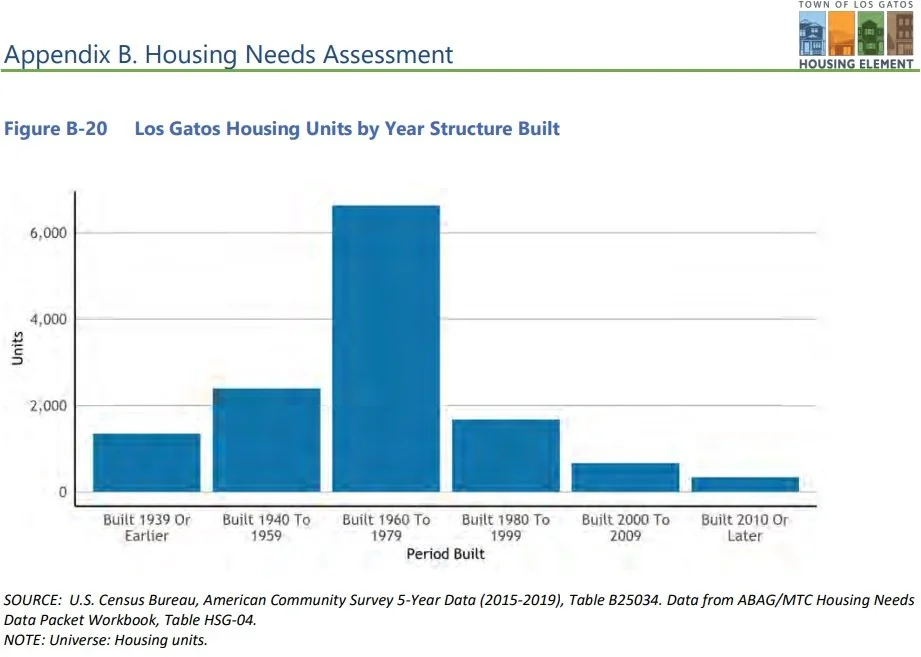

Unfortunately, we are in a supply crunch: see how home construction crashed after the Great Recession, for one thing. That would be bad enough, but the roots of the supply crunch are deeper than that. California cities’ housing elements report a home-production boom shortly after the baby boom, and close to nothing since the advent of downzoning in the 1970s.

A middle finger to modern generations, from Los Gatos’s draft housing element (p.B-23)

Today’s supply crunch is the product of a half-century of nimby policy. That’s the main problem: we can’t make up for fifty lost years in the next five. Still, housing is a basic human need, and we have to make up for as much lost time as we can. That’s the point of all the prohousing reforms that the YIMBY movement has recently gotten passed.

Klein nods at these reforms toward the end of his article, and this quote jumps out: “no one … underst[ands] the full scope” of California’s new housing laws. They’re all a work in progress, and much remains to be litigated. But it’s clear the new laws are YIMBY in spirit. That will matter when courts interpret their letter.

The Builder’s Remedy Means What It Says

One of the reforms we’re promoting at YIMBY Law is the builder’s remedy. You’ve likely read about it, and we’re getting lots of questions about how it works.

Let’s start this week with the first rule of statutory construction: read the statute. The builder’s remedy was enacted in 1990 as an intentional addition to the Housing Accountability Act (“HAA”). The remedy is available to certain affordable* developments, unless a city proves one of five defenses:

A local agency shall not disapprove a[n affordable] housing development project … including through the use of design review standards, unless … :

(1) The jurisdiction has adopted a [compliant] housing element … and the jurisdiction has met or exceeded its [RHNA]** for the planning period ….

(2) The housing development project … would have a specific, adverse impact …. Inconsistency with the zoning ordinance or general plan land use designation[ is not a “specific, adverse impact”].

(3) … [S]tate or federal law [requires disapproval] ….

(4) The … land [is] zoned for agriculture or resource preservation*** … or [needs] water or wastewater facilities ….

(5) The … zoning ordinance and general plan [required disapproval] on the date the application was deemed complete, and the jurisdiction has adopted a [compliant] housing element ….****

(Gov. Code § 65589.5(d) [italics added].) Again, the default rule is that the builder’s remedy applies, unless the city establishes one of these five defenses.

-

“Affordable,” for builder’s-remedy purposes, refers to the way California law classifies households as “lower” (well below median) or “moderate” (near median) income. The builder’s remedy applies to projects where either 20 percent of the homes are affordable to lower-income households, or else all of the homes are affordable to moderate-income households.xt goes here

-

“RHNA” is short for “regional housing need allocation,” determined with reference to “income category.” (Cal. Gov. Code § 65589.5(d)(1).) Mixed-income projects can overcome this builder’s-remedy defense if the city is behind its RHNA in any of the project’s income categories. (Ibid. [enabling HCD to “calculate[]” RHNA progress]; see also id. § 65400(a)(2)(B) [requiring cities to report progress annually].)

-

This defense also requires that the land is “surrounded on at least two sides by land being used for agriculture or resource preservation.” (Id. § 65589.5(d)(4).)

-

Cities may not invoke this defense on sites in their housing-element site inventory. Cities with bad site inventories may not invoke this defense on any residential site. (Id., subd. (d)(5)(A)–(C).)

The main builder’s-remedy defense is when local zoning prohibits the project and the city has a compliant housing element. (Id., subd. (d)(5).) Zoning often prohibits projects. Housing-element law wasn’t well-enforced in the past, but that’s changing. Over 90% of cities in Southern California missed last year’s housing-element deadline, many missed it again after the Legislature extended that deadline, and we’re projecting more than half of Bay Area cities will miss their upcoming deadline on January 31. That will take away the main defense to the builder’s remedy, meaning lots of cities without zoning.

The builder’s remedy means what it says. HCD confirmed this in an October 5 letter supporting a 2,000-home builder’s-remedy project in Santa Monica. We anticipate cities will argue that another HAA provision creates a loophole for “objective … development standards,” but the second rule of statutory construction is: keep reading the statute. The “fundamental task … is to determine the Legislature’s intent so as to effectuate the law’s purpose.” (San Jose Unif. Sch. Dist. v. Santa Clara Cnty. Office of Educ. (2017) 7 Cal.App.5th 967, 975 [quoting People v. Cornett (2012) 53 Cal.4th 1261, 1265].) And the HAA goes on to say that its “development standards” clause “shall not be construed in a manner that would lessen the restrictions imposed on a local agency, or lessen the protections afforded to a housing development project” by the builder’s remedy. (See Cal. Gov. Code § 65589.5, subds. (f)(1), (o)(5).) In other words, the “development standards” clause isn’t a defense to the builder’s remedy: it’s only for cities that have a builder’s-remedy defense in the first place.

A Special Invitation

Join YIMBY Law on Thursday at 1pm Pacific for a conversation with Dave Rand, the lawyer for the Santa Monica builder’s-remedy project. Email me for the registration link, and look forward to seeing you then.