The Cruelty of “Quiet Seclusion”

/The right to ‘establish a home’ is an essential part of the liberty guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Vill. of Belle Terre v. Boraas, 416 U.S. 1, 15 (1974) (Marshall, J., dissenting) (quoting Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399 (1923), and Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 495 (1965) (Goldberg, J., concurring)).

I’m living on airbnb again. It’s cheaper than renting, and new places are interesting. Single-room occupancy (or “SRO”) rentals were common in American history, until the Supreme Court made it OK to ban them 50 years ago. The term “family,” as in “single-family zoning,” is now specially defined in most zoning ordinances, usually to outlaw more than 2–3 unrelated people per apartment.

Look it up in your local zoning ordinance. Outside of New York, New Jersey, California, Michigan—and arguably outside Colorado, Maryland, and Ohio—it’s (for now) constitutional for your local government to define who may live together as a “family.” Contra City of White Plains v. Ferraioli, 313 N.E.3d 756, 758–59 (N.Y. 1974); State v. Baker, 405 A.2d 368, 375 (N.J. 1979); City of Santa Barbara v. Adamson, 610 P.2d 436, 440–42 (Cal. 1980); Charter Twp. of Delta v. Dinolfo, 351 N.W.2d 831, 841 (Mich. 1984); but see Zavala v. City & Cnty. of Denver, 759 P.2d 664, 669 (Colo. 1988); Kirsch v. Prince George’s Cnty., 626 A.2d 372, 380–81 (Md. 1993); Yoder v. City of Bowling Green, No. 3:1 CV 2321, 2019 WL 415254, at * 5 n.7 (N.D. Ohio Feb. 1, 2019).

Group housing matters. If land-use law were abolished overnight and it were legal to build mid-rises anywhere, it would still take years for the housing shortage to end. People’s lives change faster than that. Neither is this the first housing shortage in American history—the 1920s had a housing shortage too—and “[t]he major way in which households hit by the Depression got by was doubling up.” Jacobs, Dark Age Ahead 140 (2004). What’s happened before will happen again. Let’s explore why the old new way to provide cheap housing is against the law in most of America.

JUSTICE DOUGLAS’S “FAMILY VALUES”

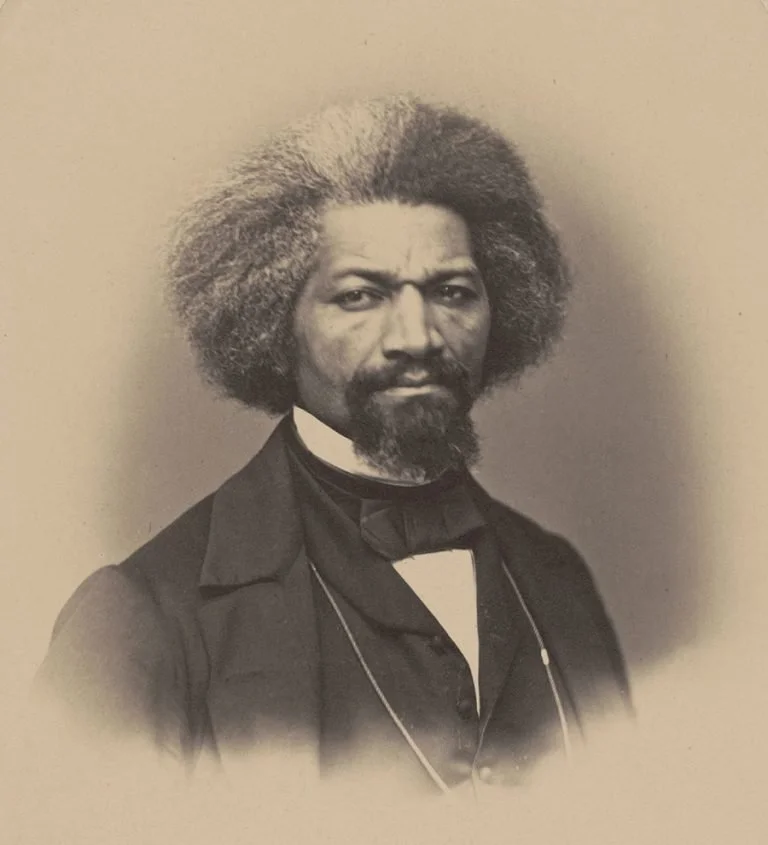

Recall, from our previous post, that the Supreme Court’s equal protection doctrine was shaped for the better by Justice Thurgood Marshall (1967–91), and for the worse by Justice William Douglas (1939–75).

-

“Apart from being a flagrant liar, Douglas was a compulsive womanizer, a heavy drinker, a terrible husband to each of his four wives, a terrible father to his two children, and a bored, distracted, uncollegial, irresponsible, and at times unethical Supreme Court justice…. Rude, ice-cold, hot-tempered, ungrateful, foul-mouthed, self-absorbed, and devoured by ambition, he was also financially reckless—at once a big spender, a tightwad, and a sponge—who, while he was serving as justice, received a substantial salary from a foundation established and controlled by a shady Las Vegas businessman.” Posner, The Anti-Hero, in The New Republic (Feb. 24 2003).

Justice Douglas wrote some howlers during his career. He wrote that federal judges should make up false facts to uphold statutory classifications. See Williamson v. Lee Optical of Okla., Inc., 348 U.S. 483, 487–88 (1955). He turned the astronomy word “penumbra” into a confusing legalism about the constitutional right to privacy. Compare Griswold, 381 U.S. at 483–85 (majority opinion), with id. at 486–99 (Goldberg, J., concurring) (better answer: the Ninth Amendment). And in his last year on the Court before a stroke forced his retirement, Justice Douglas authored SCOTUS’s stupidest NIMBY opinion.

-

It was my 2L summer roommate (2013) who taught me that to really learn a Supreme Court opinion, one should read the opinion below. But “official” PDFs of federal appellate precedents are copyrighted, or some nonsense that a better government might see fit to publish online for public access. Try your local law library, and a law librarian or a good research attorney can help you look up our non-SCOTUS citations. It’s good for your brain to read law in print format.

With that, we commend Boraas v. Village of Belle Terre, 476 F.2d 806 (2d Cir. 1973), rev’d, 416 U.S. 1 (1974).

Belle Terre was decided at the onset of SCOTUS’s second zoning fever, in the mid-1970s (its first zoning fever, again, was in the 1920s). A group of SUNY–Stony Brook graduate students, together with their mom-and-pop landlords, were cited by the fancypants Village of Belle Terre, New York, for renting a home together. The village conceded that the housemates had all “behaved in a responsible manner, and no immoral conduct on their part [wa]s suggested.” 476 F.2d at 809. No matter, wrote Justice Douglas: according to his opinion for the Court, “family values, youth values, and the blessings of quiet seclusion” constitutionally justify local restrictions on who may live together. 416 U.S. at 9.

It’s a cruel holding. People decide to room together because there aren’t enough homes to live in, and there aren’t enough homes to live in because local government zoning restrictions make it illegal to build more. Under Belle Terre, the federal courts will neither protect people from an artificial housing shortage nor allow people to protect themselves.

JUSTICE MARSHALL’S FAMILY VALUES

The best opinion in Belle Terre was Justice Marshall’s dissent. See 416 U.S. at 12–20 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

“The choice of household companions—of whether a person’s ‘intellectual and emotional needs’ are best met by living with family, friends, professional associates, or others—involves deeply personal considerations as to the kind of quality of intimate relationships within the home. That decision surely falls within the ambit of the right to privacy protected by the Constitution.”

Id. at 16. Marshall’s view prevailed, sort of, three years later in Moore v. City of East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494, 498 (1977) (plurality opinion). In Moore, East Cleveland jailed a grandmother for taking in her grandson. A four-justice plurality, including Justice Marshall, limited Belle Terre so that all “blood, adoption, or marriage” relationships enjoy a constitutional right to “establish a home” together. Justice Stevens would have struck the ordinance down under Euclid and Nectow. Id. at 513-21 (Stevens, J., concurring in the judgment). Justice Brennan, joined by Marshall, would have worded the plurality opinion more strongly:

“The Constitution cannot be interpreted … to tolerate the imposition by government upon the rest of us of white suburbia’s preference in patterns of family living.”

Id. at 508 (Brennan, J., concurring). Credit to Justices Brennan and Marshall for both understanding how “brutal economic necessity” can require “compelled sharing of a household” for many more people than some rich people think. Id. Alas, two Justices aren’t five. Belle Terre turns fifty on April Fool’s Day, when tens of thousands of Americans will be sleeping in their cars.

* * *

Belle Terre was the first in a 1970s terrible triplet of SCOTUS cases about zoning. Our next post will cover the other two cases in that triplet; then, we’ll wrap up the series with three posts on the Fair Housing Act of 1968.